Whatever it takes to survive !

(The following story is ‘inspired’ from the real life of Shri Dudhnath Tewary.)

I

Dudhnath tossed about restlessly as he tried to get some sleep. His companions, meanwhile, took turns to keep watch. For the past few days (and nights) it had been an endless cycle of running, hiding in villages and again running. The British reinforcements were hot in pursuit for they were mutineers in the eyes of the East India Company Law. They had rebelled and deserted their posts in the Jhelum rebellion of the 14th regiment of the Native Infantry.

The rebellion, later celebrated as the 1857 War of Independence had begun on a high note. They had heard about the courage of Mangal Pandey’s initiative, and they were certain that their castes were being defiled. “Were not the British providing them with cartridges greased in animal fat – to be bitten before loading ?” Dudhnath and his companions had hoped that their regiment would rebel en masse and they would join the other soldiers in their march to Delhi. It had been exactly one hundred years since Plassey and the “shatak” (century) was a good omen that Indians would be masters of Hindustan once again.

As it happened elsewhere too, there were rats who connived with their colonial masters for scraps. Their uprising was quelled in a few days. Most were captured and hanged. Dudhnath and his companions had no choice but to flee and try and make it to either Kanpur or Lucknow which were becoming nerve centres in the War for Independence being waged.

However, fate willed otherwise. He had dozed off and so had his companions. He was awakened by the pointed poke of a bayonet and kicks to his behind. As he opened his eyes, he saw dozens of soldiers around him and his companions – rifles aimed and ready to shoot. For him, the War was over even before it begun!

II

The next few weeks were a nightmare. They were tortured, physically and mentally. He saw many of his companions being brutally hanged in public places. For some reason unknown to him (as he did not understand a word spoken at the summary military trail) he was not hanged but given a sentence called “transportation for life”. A native soldier, on the right side of the Company, gleefully explained it to him quite succinctly – ” Off you go to a faraway island which the British are using as a prison. It is scarcely populated; the weather is hot and humid and there are cannibals in the jungles waiting for treats like you from the mainland. And you will definitely lose your caste as you cross the Bay of Bengal. The best part is, that this will be for life. There is no coming back. Enjoy the rest of your miserable existence in the Godforsaken land. The only redemption is that probably you will not suffer long enough – tribals, animals, weather and the prison will take you out very soon”. Dudhnath, shuddered at the thought. Was this the price to pay for fighting for his own country?

III

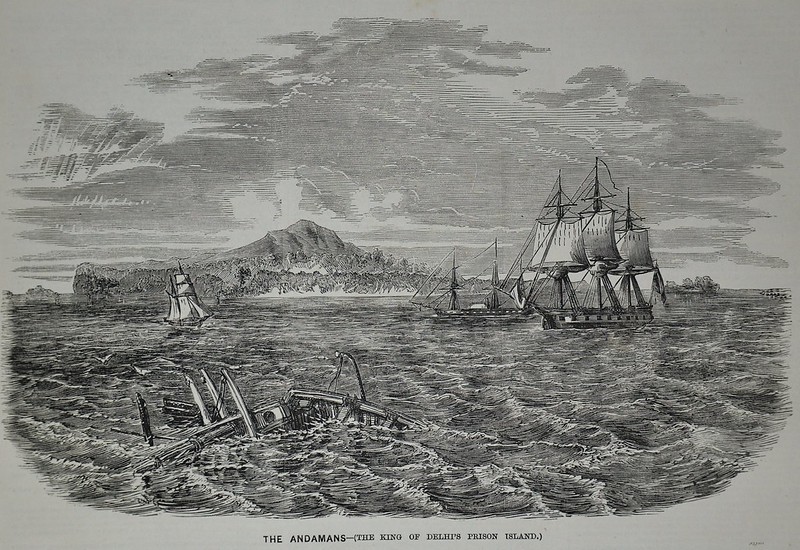

Dudhnath was sent to Karachi and finally after six months since he was first captured, he was shoved onto the ship Emperor Roman. Dudhnath, a poor sepoy, was ignorant of world history to realise the irony – a ship named after an empire which had dominated Britain itself. Roman Emperor set sail from Karachi to the unknown beyond….

IV

He reached the Andamans after an agonising journey in iron fetters. The sea crossing had been horrendous. He lost his caste and vowed a Mahamritunjaya Yagya (sacred religious ceremony) when he would go back home. Yes, he would go home one day he mused. The black waters of the Bengal Bay would not be his death. No amount of “Kalaa Paani” would stop him from going back. He was a survivor.

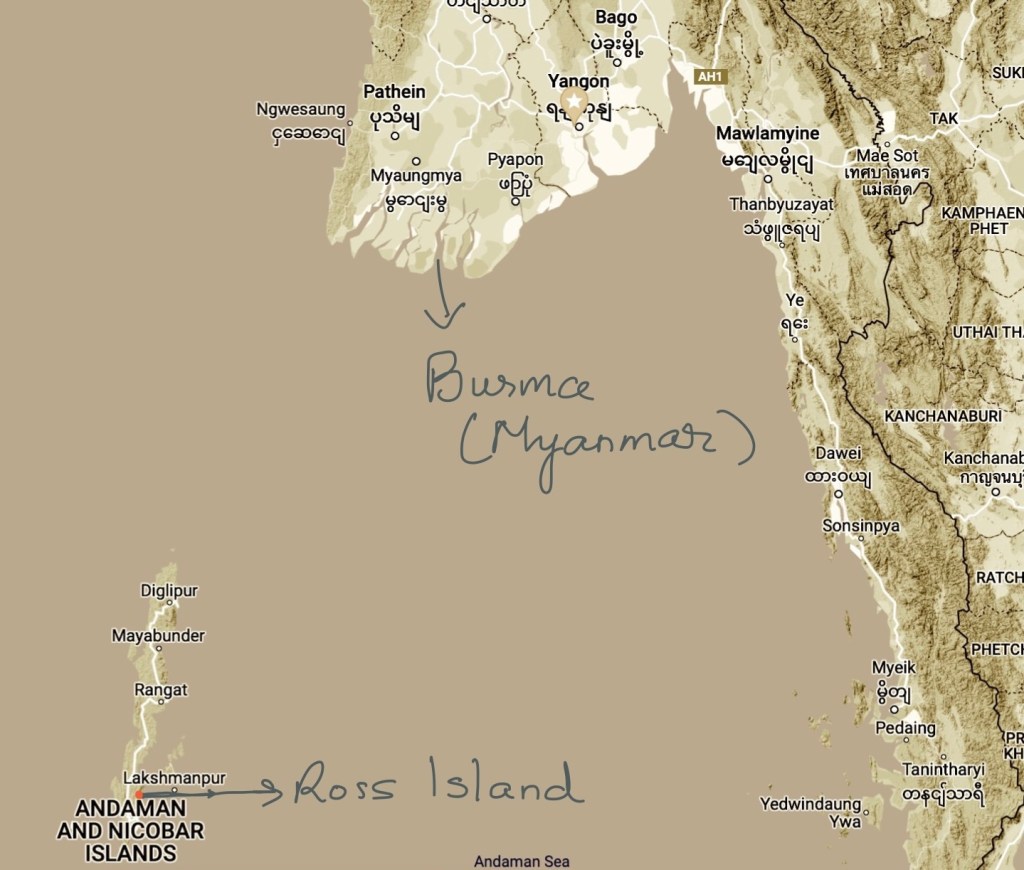

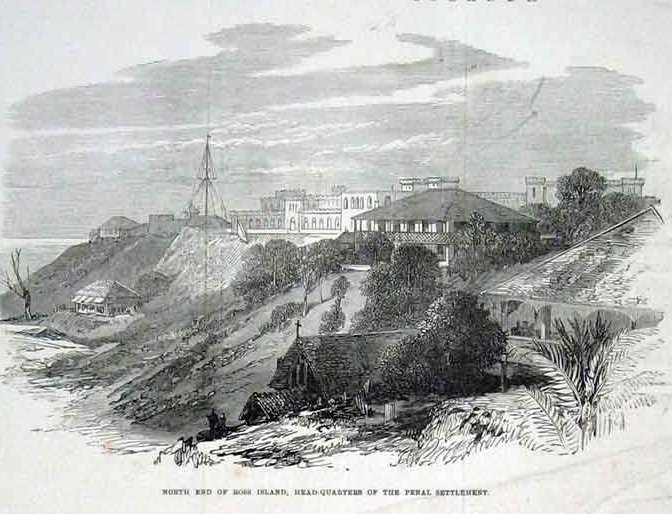

Along with him were other convicts, most of them warriors like himself. He was given a number “276” at Ross Island. Life was oppressive as promised. Insects buzzing around, fresh water was scarce -the only source being rainwater stored. They had to do manual labour – which included cutting tall trees whose wood was so hard, that their axes often broke. Within a week, he was fed up. He started conversing with other convicts whenever he got a chance and soon found out that an escape was being planned. He immediately agreed. They surmised that that the land which they could see beyond the island was Burma (present day Myanmar) and the local raja would support them in their bid to go back to India. After all Burma had suffered two defeats in 1826 and 1852 at the hands of the British and would still be smarting from those blows to their sovereignty and prestige.

Ninety odd convicts were soon onboard. They secretly made rafts using felled trees and bamboo. A sympathetic Indian guard had a whiff of the impending plan but kept quiet. After a few days, the rafts were ready and hidden at the shore. When the sun was down, and the guards were lax, they silently and stealthily made it to the shore in batches. They took with them pots of drinking water, rice and some implements for protection and travel. They pulled out the rafts on to the channel and started rowing quietly hoping to reach the ‘mainland’ a few kilometres away in quick time. They did that, barring a few mishaps including a raft capsizing and a convict being pulled into the water by a huge fish. Though they did lose a considerable portion of their rations with the raft, they were more relieved than exhausted as they pulled up onto the beach and hid in the undergrowth beyond. A few were asked to keep watch while the rest dozed off happily – after all they had won their freedom.

V

Dudhnath woke up to the sounds of pleasant chirping birds and irritating mosquitoes. The sun was up and fierce. The azure blue transparent sea offered little solace. They quickly drank some water from their rations and decided to head inland towards Burma. The were greeted by dense forests with trees as tall as their gaze could go. Sunlight scarcely peered through, and the ground was an undulating landscape of roots, shrubs, vines and ferns. They trooped northwards, but soon lost sense of direction or time. After two days of painstaking progress, they heard the sound of humans. It could either be the Islanders, whose aggression and hostility were folklore, or the British who may have sent a capture party to take them back. Thankfully it was neither. While they got ready with their axes and knives, they were confronted by – another batch of escapees, about forty in all. They hugged each other and soon found out that they had escaped the Viper and Chatham Islands and were also on their way to Burma. With renewed enthusiasm, the hundred and three dozen odd band of fighters, set off again in their flight to freedom.

VI

Duthnath knew something was wrong. They had been walking for two weeks and Burma was still not in sight. The jungle did not thin out and the same formidable trees, irritating insects and cacophony of birds persisted. Wherever they went, they were confronted by sea, and they soon realised that they were on a large Island rather than any mainland. They ran out of whatever rice they had, and the pots of water were soon empty. There was no rain and a few who drank from the sea retched and were left to die. They could not carry the sick to hinder their progress. A few climbed the tall trees and used the axes to obtain water stored in the branches and climbers. Some water was also obtained from rivulets on the sides of the hills. But they were soon hungry and thirsty, and their heat was adding woe to their worries. They also found a few huts which they believed to be of islanders but thankfully there were no “savages” in sight.

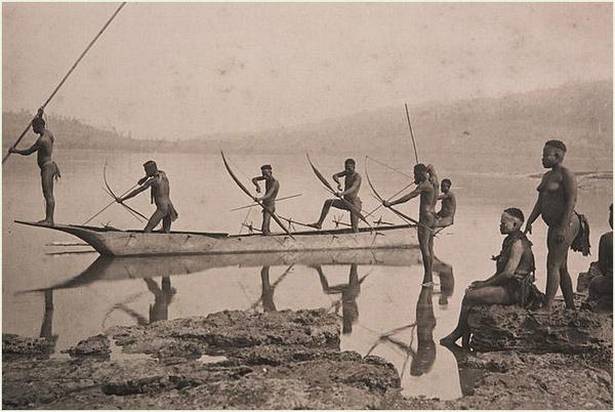

However, luck soon ran out and as they were walking through the jungle, they were confronted by almost an equal number of native islanders. All armed to teeth with bows and arrows. Resistance was useless and so they prostrated themselves in an act of clemency as word of the tongue was useless. The natives, however, maybe captives of their past experiences, attacked the escapees from all sides. It was as if orders had been issued to leave no quarter.

Dudhnath was hit thrice, in his shoulder, elbow and around his eyebrow. He somehow managed to flee the carnage and as he dashed through the undergrowth, he heard the cries of his fellows as they were mercilessly slaughtered. After running for ten minutes, he was joined by two other escapees. Quite sure, that they were not being followed, they sat down to recess their hopeless situation. Burma seemed as far as India now, and going back to Ross Island would mean a certain hanging by the noose. The Islanders had shown their intent and so another confrontation with them would also mean death. So, they decided to go the shore, build a raft and hope to be picked up by a ship from a friendly country be it Burma or Siam (Thailand). Or maybe an Indian princely state vessel, not under the East India Company flag, could pick them up if they were lucky. If nothing else, they would scourge the numerous islands and try to settle on one where there were fewer hostile tribes or were uninhabited.

So, the three of them, trudged along a saltwater creek which led them to the shore. And there, as if fate was still not done playing mischief, they stumbled headlong into a group of islanders who were drawing up their canoes after a day’s hard work at sea.

VII

Dudhnath gathered his breath as he looked around. The past fifteen minutes had been horrendous. They tried to flee but were cut off by the group which numbered up to fifty souls. The hapless three prostrated with folding hands and pleaded for their lives, but his two companions were killed from arrows straight to the heart. Dudhnath spied a hole under a fallen trunk a few meters away and dived headlong after breaking out from cordon. Now in this hole, he could sense the group waiting for his next move – which was none. Dudhnath had no options and death was now a certainty. He wished he was killed on the battlefield rather being subjugated to the ignominy of being killed by a non-white. He gingerly brought out a foot, but a flurry of arrows came through, one scratching him in his thigh. He then came out headlong, with his hands folded in supplication, with an endearing look at the group. He closed his eyes and muttered the Gayatri Mantra, remembering his parents as he waited for the arrow to pierce his heart. However, much to his surprise, no fatal blow came. Dozens of arms dragged him out and carried him off to their boats. Dudhnath had survived again, for now….

VIII

Dudhnath, not only survived that day, but thrived as days turned to months. He assumed that he had been accepted in the tribe as he was neither killed or confined. He was shorn of his clothes and hair shaved from his head. He went around from island to island along with the group, who led a nomadic existence, camping at one site not for a prolonged stretch of time. He ate the same food as them (no, they were not cannibals) and slept in the same clearings. He was taken on hunts though he was not allowed to bear any arms. They would make forays into the jungle but always come back to the seashore at sunset. He picked up a word of two of their language and as days went by, his fears started to dissipate. His wounds soon healed, helped by the pastes applied by the tribals, made from roots and herbs. He regained his strength. He was amazed to see the agility of the Islanders, their love for family values and their organisational skills. Life was not luxurious but was comfortable as it could be in the surroundings. It was not all death and illness as he had often heard in India. These were human beings, just like any other race, proud of their kin and their surroundings. However, they were extremely protective about their habitat which explained their hostility to external interferences. One day an elder, called him out and pointed his daughter towards him. A clearing was made in the center of their current camp, and he was made to sit with her. He had seen this before and knew he was being married to the elder’s daughter called Leepa. They sat quietly for a few hours as was the custom. They still did not trust him, as there were no bows or arrows in the middle as was the norm for the ceremony. By evening, he supposed that Leepa and he were husband and wife.

IX

It had been many months since Dudhnath had escaped and had been captured by the Islanders. Throughout the year, he visited many islands along with his newfound kinsfolk. He was married five times, each ceremony taking place exactly the way it was performed the first time. Still no bows and arrows! He grew accustomed to the life he was leading but he knew that this was not home. He was still a prisoner of the islands. The fact that there were no chains, and the masters were not white, brought him little solace. He yearned for his village, his farm with large swathe of paddy swaying in the wind, and most of all, home cooked food prepared in ghee by his mother. The familial bliss attained in the last one year could not overcome the pangs of separation from home. This was not home away from home. But what could he do? He could not escape as he had still not sense of geography, nor was he willing to risk his life with a confrontation with another group who may not be as merciful as this one. Dudhnath did not share his thoughts with anyone. The language barriers made it quite impossible to communicate the simplest of things, and anyways they would not understand what he felt. Biding his time, Dudhnath continued to go about his life in the jungle.

X

Dudhnath could see the mighty Ganga in the distance. His friends were jumping into the water to escape the pre-monsoon heat. He could smell the whiff of milky tea and piping hot samosas. He extended his arm to grab one, but something was wrong. The landscape rapidly turned green and the gastronomic whiffs faded away. He woke with a start to find that his “wife” was gently shaking him. She motioned him to get ready. So much for his samosas, he cursed. A few minutes more, and he would have eaten one too, even if was in a dream. Soon he joined the rest but this time he observed that a few other groups had gathered and there was an unusual excitement in the air. The armoury which included bows, arrows, crude axes and spears were also more than would have been required for a daily hunt and seemed that preparations were on for a long time. Maybe they were planned an inter-island raid he speculated.

He went with the menfolk and got onto the boats. It was still quite dark, and the sun had still not risen from the sea. But something was wrong, instead of going to the other islands they were heading in the direction from where it all began – they were going towards Port Blair and Ross Island. And soon there were canoes from all sides, and they were now numbering a thousand, not a few hundreds. Dudhnath had picked a bit of the local dialect in his yearlong sojourn. He soon realised he was part of an attack party, and the target were the British. As they neared Port Blair, Dudhnath’s gut churned. Yet another battle, where death would again be lurking around the corner. He relished the prospect of killing a few colonialists, but what if he was killed? And even if he did survive, he would be back to the jungle, eking out a life in the humid jungle, waiting for the next battle. He had seen the viscousness of the British, and he knew that they ultimately would prevail over the Island. What if he was captured, during the battle, then death as a fugitive convict was even more certain. Dudhnath, the survivor, mulled over his options and gradually a sketchy plan began to take shape. It was risky, but he was convinced that this was for the best, whatever the consequences.

XI

The Islanders silently converged near Port Blair. They were seething for revenge against the Whites and their Brown lackeys who had been cutting down their beautiful habitat. The land had been theirs, for times immemorial. They had resisted the Malay pirates centuries earlier and also the curious savage explorers who had taken some of their kin in chains. More than seven decades ago, they had successfully ensured that the first white settlement did not take permanence and so this time too, they would prevail. They had taken in this brown native, despite pleas from older folk to show no mercy. However he looked harmless and had integrated into their tribe while they still kept a close watch on him. ” Never trust the outside man” had been the mantra that had been passed on through generations. They brought him along for the attack, as they did not want to leave him behind with the women. They all thought him of a dull pitiable soul, so one more to the party did not make much of a difference.

As they neared the barracks, Dudhnath jumped into the water and went beneath the surface. It was dark enough and thus the Islanders on the boat couldn’t pinpoint his location. Still, he remained submerged and swam away from the boats with all the strength he could muster. An occasional arrow came zipping in for a minute after he jumped, but then there was silence. Thankfully the fishes or the crocodiles must be sleeping, and he did not meet a watery grave. After twenty minutes, he reached the shore and ran to the Office of Mr. Walker, the superintendent. He knew he may be running to his death, but he ran on and on…

XII

Superintendent Walker was grumpy. His dinner had been more like the gruel offered to Oliver Twist. Life in the Andamans had taken a toll on him. Away from what he called civilisation, it had been an endless rigmarole of disciplining convicts, manning his disgruntled soldiers and thwarting the Islanders who were resisting attempts of colonisation. He had just finished his morning tea when an unkempt man came running to his office hotly pursued by two guards. The person who tumbled in looked like a cross between a Hindustani and an Islander. He was in the elements of nature with barely a few scraps of barks and leaves on him, his head was shaved, and his body had tattoos, the tell-tale of the tribes. The guards apprehended the person and roughly searched him for arms, but he was clean. Walker had seen this guy somewhere but couldn’t place him immediately. The usual course of action would have been instant arrest and interrogation later, but the terror in the eyes of the person and his pleadings made Walker curious. Motioning to his guards to pause, he asked the fellow to slow down his blabbering and make sense. For the next half hour, Walker’s eyes widened in astonishment as Dudhnath recounted his extraordinary story.

XIII

The confrontation with the Islanders that day would come to be known as the Battle of Aberdeen. Dudhnath’s timely warning enabled the colonists to divert and concentrate crucial resources and thwarted the biggest challenge yet so far to their authority. The exploration, expansion and exploitation of the Islands continued unabashedly in the years to come, and the Islanders were not able to mount an attack of this scale ever again. The Administration recommended an unprecedented pardon to Dudhnath, who otherwise would have gone to the gallows as a recaptured convict. Delhi, in order to demonstrate the benevolence of Imperial rule, made an exception and granted the “Hero of Aberdeen” his freedom. Dudhnath’s exploits became a topic of dinner parties from Lucknow to London and a subject of many weeklies and journals. He returned to his village, a legend. He had thrice survived – the rebellion, the Islanders and finally the gallows and thus was thrice reborn. An elaborate religious ceremony regained him his caste too. He regaled the young and old with his “heroic stories” on the banks of the river Ganga, while munching his hot samosas along with milky sugary tea. The Administration kept an eye on him for some time but realised that he was past his prime and had his life’s worth of excitement. Though they did occasionally call him for cross referencing the elaborate records that they were keeping on everything – including the Andamans.

XIV

Dudhnath was summoned once more, but this time requested (more like a direction) to go to Andaman to help the local administration in some anthropological/scientific mission. His time with the Islanders would provide invaluable information to the scientific team stationed there. He travelled across the Bay of Bengal once again, this time without fetters and in relative comfort. As the islands loomed before him in the horizon, he had a feeling of dread which he could not explain. Port Blair was expanding, and the British were firmly in control. He was taken to a group of Islanders who were being “civilised”, and he recognised a few women from the group with whom he had stayed during his sojourn. He learnt that Leepa had given birth to his child. Leepa was there too, she did not say anything, just came to him and spat in his face. The disgust on the faces of the Islanders made him shudder. Obviously, thereafter there was no further conversation with the group. Dudhnath the survivor, quietly walked away. The rest of his trip was uneventful, and with mixed feelings, he returned home.

XV

The churning within, kept Dudhnath awake for many nights. His happiness of surviving the ordeal was now laced with pangs of guilt. As he grew older, his stories were soon forgotten, consigned to the appendices of history. India would have much bigger things to ponder – the national movement, mass mobilisation by Gandhiji, revolutionaries, and eventually partition and independence. Dudhnath did not have the luxury of foresight but knew that one day the Islands along with Hindustan would be free. He fervently prayed that history would not judge him harshly. He hoped that free Hindustan would take steps to preserve the indigenous people and their habitat. That would be his atonement. That would be his deliverance.

The enigma called Dudhnath Tewary by Dr Neil Jain is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Leave a comment